What are the Foucauldians Dreaming About?: A Review Essay of Behrooz Ghamari-Tabrizi’s Foucault in Iran

By Karl Fotovat

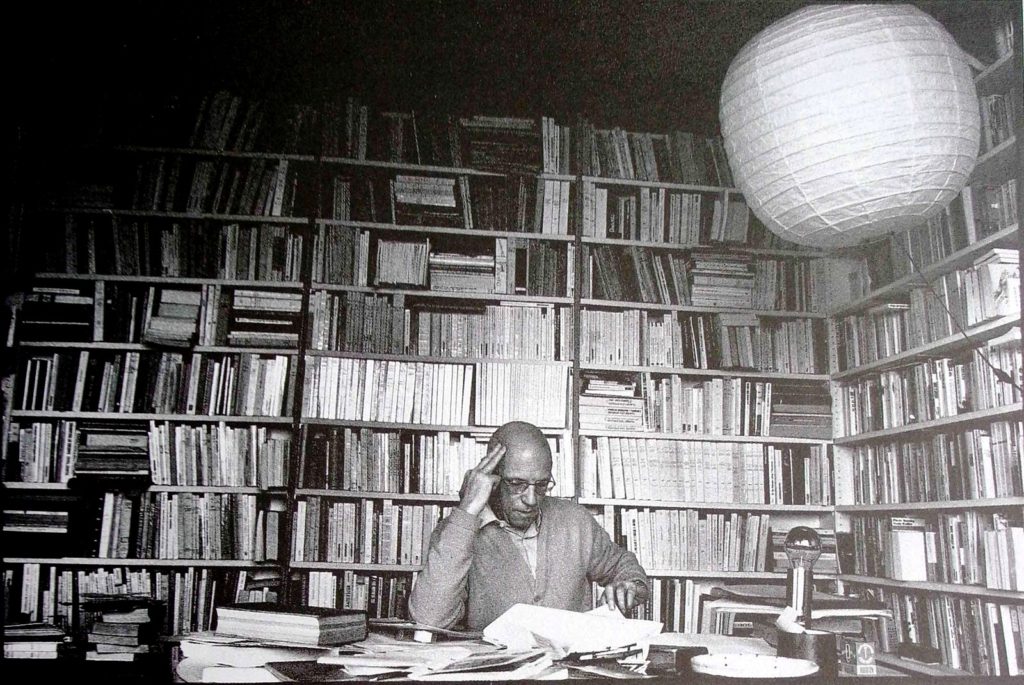

Michel Foucault (1926-1984) was a French philosopher and self-described historian of ideas who made key contributions to the post-WWII intellectual landscape in Europe and the United States. Since the 1970s his thinking has informed, shaped, and even redefined intellectual discussions in fields as far reaching as sociology, pedagogy, queer theory, and prison reform. He is most widely known for the “genealogical” works of his middle period (most notably Discipline and Punish and the multi-volume History of Sexuality), in which Foucault rendered a pessimistic account of modernity as characterized by repressive forms of social mediation and cultural identification parasitic on everyday modes of individuation. Socially pervasive and intricately interlaced power dynamics remain obscure to overt channels of partisan criticism and, increasingly, beyond individual attempts to resist them. The eponymous adjective “Foucauldian” continues to orient contemporary attempts by urban intelligentsia and the campus Left alike to rethink relationships between knowledge, power, and ostensibly non-political, everyday practice.

In light of this far-reaching impact, Foucault’s unconventional enthusiasm for Islamic protesters following his 1978 journalistic visit to Iran—just days after the Black Friday massacre—has become difficult for today's Left to own. As hindsight and leftist “wisdom” continue to broaden, few have succeeded in reconciling the Foucault of Discipline and Punish with the Foucault who documented a few bloody weeks in revolutionary Iran. For those interested in Foucault’s oeuvre and those interested in the Iranian Revolution, a few questions have assumed importance:

Particularly with regard to direct acts of mass protest, how can we reconcile canonical Foucault's ultimately cynical derogation of resistance with journalist Foucault's apparent subscription to resistance as an effective motor of world-historical geopolitical change?

How do we make sense of Foucault’s alleged “return to Kant” during his late period, i.e. the period immediately following the Iran visit and forming a subtle break from his genealogical period (and both these differing from the early, archaeological period)?

Can today’s Left “forgive” Foucault for supporting a political movement whose ultimate trajectory was (and remains) repressive towards the marginalized groups whose experience Foucault’s work sought to uncover? Shouldn’t he have been slower and more cautious to endorse the populist elements of the movement’s budding agenda?

Question #3 forms the basis of Janet Afary and Kevin Anderson’s 2006 Foucault and the Iranian Revolution: Gender and the Seductions of Islamism.[1] Their overall thesis is that Foucault was “seduced” in the moment by the potential or promise of a non-Western, non-modernized, “archaic” “Islamic government” and that, once properly and retrospectively recontextualized, his sins are clear for all to see. This is a provocative thesis, but it uncritically assumes a secular lens through which Foucault’s conspicuous lack of cynicism can appear only as naive, and not as the intentional adoption of a different mode of criticism altogether.

Behrooz Ghamari-Tabrizi’s Foucault in Iran[2] addresses each of the questions above, but it distinguishes itself foremost as a welcome provocation to Afary and Anderson’s labeling of Foucault as an unwitting, “bad leftist.” He does not set out to exonerate Foucault, but by reorienting the Iranian visit in light of a particular methodological puzzle, Ghamari-Tabrizi is able to problematize leftist presumptions and render question #3 above moot. He sees the following methodological question—Foucault’s own guiding question during the Iran trips—as both more valuable and less examined: is it possible to report back to the West what is happening,[3] i.e. is it possible to document a history of the present?[4]

The Question of Resistance

Despite his reputation as a theorist of power, Foucault’s claims about power are nowhere self-contained nor systematized into a theory, but we can note a few key principles that underlie the common understanding of the relationship between power and resistance in Foucault: 1) any attempt to forge a resistance to power implicitly acknowledges its authority and thus extends the reach and dominance of its principles, thus 2) power appropriates and even thrives on attempts to resist power, resulting in its consolidation.[5] Finally, 3) because power (often) assumes discursive forms, then by transposing strategies of power/resistance onto discourses of power/resistance, we arrive at a theory of discursive closure: there is no “outside of” discourse, and whatever emancipation a given counter-discourse offers up is illusory.

Also key to the genealogical works is the thesis that subjects are produced by discourses, which when wedded to the thesis of discursive closure, lands us all in a suffocating idealism, where “resistance” lies in little more than shuffling our vocabularies—though also (and this is usually not stressed enough) changing our commitments to them. If power and discourse are coextensive, and their reach is total (meaning the closure thesis holds), then whence resistance? Whence subjects who might resist? Whence subjects free enough to choose resistance?[6] And finally, the great paradox of freedom, so painfully relevant to the legacy (if not the basis) of the Iranian Revolution: whence subjects free enough to choose, e.g., even their own submission to the most repressive regimes?

For the many that find Foucault’s power narratives compelling, his standard reply to the question of the subject in the power-resistance dilemma is less than satisfactory. The issue is perspectival, says the genealogical Foucault: at issue are discursive forms and so he begins from a positivist assumption of discourse as the object. And this is not untrue: Foucault’s works are anti-normative in tone, merely reporting the strengthening of strains of power and their intermittent confluences into more dominant strains. The archaeological and especially genealogical Foucault is committed to a minimal methodology of “laying bare” the facts in their disparity, and allowing the reader to determine herself within the discourses that result. There is no recognition of ideological capture, no demand for liberation, no call to action; there are only the contingencies of discursive transformation. For a theorist who essentially politicized the non-political and everyday, and whose intellectual climate was awash with the grand narratives of structuralism, psychoanalysis, and various communist factions, there is little if any endorsement or overt engagement with partisan politics to be found.

At the start of the Iran visit, Foucault clarifies his method of laying bare with the added proviso that because he emphasizes contingency within discourse, readers are free to develop strategies of attack and resistance against power.[7] Apparently by destabilizing and problematizing discursive structures, readers will shift from assuming their ontological permanence to realizing their contingent, if complex, historical formation. This tacked-on optimism is also dissatisfying, but Foucault would sooner accept these minimal terms of engagement rather than dictate what kind of subjects we ought to be. The “subject” “trapped” within the winding threads of the genealogical works is more the successor of the Freudian ego than the Cartesian one—unless it is the paranoid, self-doubting Cartesian ego of the Meditations, prior to finding God.

Political Spirituality

After the archaeological and genealogical periods, Foucault’s oeuvre becomes increasingly anti-systematic, reflecting a constellation of concerns about subjectivity: philosophy of the present, care of the self, and the hermeneutics of the subject. In particular, the essay “What is Enlightenment?”[8] stands out as a valuable but surprising engagement with basic Kantian tenets, where the great systematizer is recast as the Kant of small, simple, but vigilant acts of self-improvement; from a Kant of the infinite and universal to a Kant of the Now. Afary and Anderson seize on this text in particular as containing Foucault’s coded contrition for the uncritical enthusiasm from the Iranian Revolution era.[9] For intellectual biographers, the “return to Kant” has been gauged as either a retreat from theory or a sobriety from it through the simplicity of basic acts—the care of the self, the hermeneutics of the subject. But the “return to Kant” is hardly a return to Kantian doctrine, and instead a reignition of a, for Foucault, lost Kantian impulse. The concept of Enlightenment becomes enlightenment, a call to action, in the present, that is a tri-phased and ongoing commitment: first commitment to liberate oneself from one’s self-incurred tutelage,[10] resulting in a commitment to pay the price for one’s newfound subjectivity,[11] and thus finally a commitment to redefine freedom and reform the newly transformed landscape of freedom that arises from this liberation.[12] There is a dynamic (dialectic?) at play here often overlooked when we think of the canonical, architectonic Kant—if the system was his only and highest aspiration, Kant would have stopped at the first Critique! So the transformation of the Kantian system into a Kantian drive is neither a simplification nor a call to think the Kantian discourses hermeneutically, one atop the other, as it were. It is the recognition that only something like a dynamic subject (and a tragic one, at that) can realize the project of modernity: enlightenment.

Afary and Anderson hold that Foucault was seduced by a non-modern, “archaic fascism” when writing the essays on the Iranian Revolution, and that the “return to Kant” late in his life was a sober acknowledgment of that. Ghamari-Tabrizi advances the novel thesis that Foucault in fact reads insights from the Iranian Revolution back into his thinking about Kant,[13] making the reconfigured Kantian impulse from the late essay a figure with robust enough conceptual resources to give voice to what Foucault saw in Tehran’s streets—the collective will. Quoting Foucault:

The collective will is a political myth with which jurists and philosophers try to analyze or to justify institutions, etc. It’s a theoretical tool: nobody has ever seen the “collective will” and, personally, I thought that the collective will was like God, like the soul, something one would never encounter. I don’t know whether you agree with me, but we met, in Tehran and throughout Iran, the collective will of a people. Well, you have to salute it; it doesn’t happen every day.[14]

The point here is not that Foucault finds astonishing the living, concrete embodiment of what, for first-world political theorists, exists only abstractly; the collective will can be found at demonstrations and protests the world over. The point is that the “will” Foucault witnessed was indeterminate, closer to a negative will (“not this!”)[15] than a “will for” legislative reform, concrete concessions, etc. Its character was also profoundly subjectivating, in the sense that there was in the air a collective desire to become a new subject, and even to risk one’s life rather than maintain the Pahlavi regime. This subjectivating power, this acceptance of self-transformation, to a subject one never thought capable of becoming, and this at risk of death—this is no mere collective will. In the Iranian writings, Foucault coined the term political spirituality to account for this marriage of communal desire, possible self-sacrifice, and deepening march into political risk for the sake of a shared recognition of a commonality of will.[16]

The cynical, Parisian intellectual would remark that the protestors were hardly united in their intentions and carried with them (if at all) heterogeneous and conflicting utopias; all mass political allegiances are mere and momentary marriages of convenience. Afary and Anderson make this a point of admonishment! Foucault says he can already hear the French intellectuals laughing at his insistence on the novelty of the moment.[17] But this “revolutionary” moment need not be entirely novel,[18] just distinct from the European Enlightenment: following Shiʿa doctrine,[19] it enfolds religious insight into this project of enlightenment, it is a negative will, but strangely also a (negative) will unto death.[20] The journalist Foucault, aiming at a history of the present, was at a loss to find predecessors of this will elsewhere in recent history.

And this, perhaps, because for a history of the present, the point is not to locate one’s predecessors, nor to taxonomize the wishes of a people under the categories of Western history, nor even to leap ahead and articulate for their sake the principles they are (truly) seeking in regime change. The Kant of the third Critique is instructive here, whose obsession over the possibility (and necessity) of singularity led to a puzzling volume covering topics as vast as teleological histories, natural evolution, non-figural artworks, and natural beauty. The political spirituality Foucault witnessed in Iran was essentially singular: unique and individual in its instance, universal in its address.[21] This was too much for the May ‘68 protestors of the French intelligentsia to accept, now ten years more adult. The Western Left regarded the Iranian protestors perhaps as brave, but certainly naive, for thinking to push back the inevitable tide of market imperialism through a populist Islamic revolution; there was a price to be paid, intellectuals would admonish, for subscribing to the “wrong” (i.e. anti-liberal democratic) progressivism. The naïveté of both wishing to step outside of History and yet daring to act as a world-historical agent of History was unforgivable.[22]

Lessons from Kant’s third Critique, as well as those from more recent successors, are very much alive here. The notion of paying the price for one’s new (or even newly sought-after) liberation is thematic—we can build up our understanding of man, but lose that of God in the process; we can educate the individual, but at the expense of cultivating the community, etc. The terrain is everywhere risky: it cannot be known in advance which strategies will be successfully transformative or enlightening, and which are doomed to backfire. Could a traditionalist, anti-modernist government even work? In Iran or elsewhere? Haven’t we as intellectuals chosen the “right” progressivism and thus proven the absolute wrongness of all others? There is actually a surprising shift away from absolutism in the third Critique: the Kant of concepts and categories, of maxims and principles, becomes the Kant of exemplars. Exemplars express singularity, and they defy categorization, conceptual determination, or strict adherence to an antecedent rule or guiding principle. The mind’s efforts to subsume an individual phenomenon beneath a universal fail, and this failure becomes instructive in the mind’s developing new and novel categories (why some readers think Kant’s three Critiques should be read in reverse) that might be adequate to the address of the singular individual phenomenon calling out for recognition. We say “might” be adequate because the new understanding of the phenomenon might be wholly private and unshareable, thereby not apt for a shared conceptual language. There is always the risk of total loss, total rejection, or total incomprehensibility when we attempt to forge novel concepts. Kant famously chooses natural beauty and purposiveness as examples, but we can add Husserl’s eidetic intuition, Quine’s examples from his discussions on the indeterminacy of reference, Wittgenstein’s private language “arguments,” or any number of examples from the histories of ancient and modern skepticism as illustrating this risk at play in meaning. And this skepticism was the de facto rule for the French intelligentsia in the face of the events Foucault attempted to document. Where cynicism and skepticism meet, it might be said (we can include the present day here), history seems unlikely to progress.

Against the Left’s Obsession with Theory

According to Western intelligentsia, the Iranian Revolution represented the capture of a potentially beneficent call to action among varied actors (but primary potential leftist allies) by a repressive and regressive religious regime. Its failure was, for many, obvious from the start. Intellectuals of every stripe had a hand in doubting the revolution: it was “too populist” to erect competent leadership, it was “too religious” for Iran to win needed diplomatic currency, it was “too isolationist” to defy the pressures of global capital, it was “too patriarchal” to inspire liberal democratic allies, etc.

When posed with the question "what is happening?" the academic Left seems all too often ready to answer with the (Western historical) master narrative of its choosing. Sometimes these narratives are modified usefully, and sometimes this work conveys some subtle insight. But the contemporary left theorist seems to have a difficult time listening to, or attending to, what is happening in itself, as it were. The entire art of academic explanation is premised on the virtues for wisdom of ever greater and more persistent contextualization, but the actual outcomes we witness seem to be that of reduction: of lodging the moment of interest within the greater or grander narratives until it appears an obvious part and logical outcome—perhaps shearing the moment’s edges of pesky bits of individuality or singularity where necessary, where the object “pushes back,” as it were. Contextualization works best retrospectively, but is today’s left theorist satisfied with limiting herself to a backward-looking post? Hardly. But contextualization as a predictive model, projected forward in time, tends embarrassingly toward reduction and the failure to recognize novelty. It takes little humility to say: we cannot know in advance what will arise from a Ferguson, from a Baltimore, from a Tahrir Square. Yet statements like these are rare in “serious” criticism. As theorists we are too ready to subsume the particular under the general. We indulge our cognitive powers with what Heidegger called metaphysical thinking or what Adorno and Horkheimer called identity thinking. From these exercises we pretend to derive much explanatory power... but at what cost?

So what, then, is Foucault’s point in attempting a history of the present? Ghamari-Tabrizi refers to a beautiful passage from Power/Knowledge where Foucault discusses the kind of criticism, and kind of intellectual, he dreams about.

I dream of the intellectual who destroys evidence and generalities, the one who, in the inertias and constraints of the present time, locates and marks the weak points, the openings, the lines of force, who is incessantly on the move, who doesn’t know exactly where he is heading nor what he will think tomorrow for he is too attentive to the present...[23]

This is an enigmatic intellectual, in the cast of Benjamin or Blanchot; one who espouses a relationship to the living moment that more closely resemble an ethics of close reading, alive to the pushes and pulls of the text and its unexpressed potentials, than the structuralist methods of taxonomic classification of texts in vogue among Foucault’s Western contemporaries. But Benjamin and Blanchot are markedly obtuse; are they even valuable exemplars in this path to a different criticism? We might get some more help (but very little… almost nothing) from turning to Adorno’s notion of negative dialectics as that method of analysis that insists on the persistence of the nonidentical within the identical.[24] But this all leads us to ask: does Foucault’s dream intellectual even exist today? Anywhere? If so, who is her audience? What is her impact?

Foucault’s is a welcome provocation, but I wonder how successful this possibility truly is, particularly after the resurgence of grand narratives following the fall of the Soviet Union and (for entirely different reasons) after 9/11. More than ever, the academic Left’s commentary has gained traction by contextualizing each of its objects—whether they be political scandals, geopolitical conflicts, or movements of global capital—as another within a legible series of unjustified acts of violence. Doesn’t sacrificing a little singularity help us get at the historical substance of the stuff? And wouldn’t insisting on that singularity, on the object’s non-identicality with its apparent forebears, risk reducing criticism to mere reportage, fetish, or the merely commemorative? It risks becoming irrelevant altogether if stripped of its explanatory power, at least according to the prevailing norms of academic analysis and inquiry. Doesn’t this at least seem dissatisfying to us theorists? Didn’t Foucault himself become irrelevant to any discussion of post-Revolution Iran?

There is an inherent risk in calling on a different criticism, and at least some collateral risk from backlash by the academic Left itself. But I think the risk is entirely the point. As a kind of paradoxical (or perverse) inversion of Marx’s most notorious thesis on Feuerbach (“philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways; the point, however, is to change it”), the power of this method lies in its minimalism and its powerlessness. We can no longer grant that today’s theorists know what, where, or when to interpret. By contrast, in expressing its own limitations, a different criticism pleas for both recognition and action from outside of itself. (But, as a pessimistic coda, in its very powerlessness to explain the phenomenon, this criticism risks failing to account for its import, its relevance, or even its allure.)

What cannot be denied, says Foucault, is that a remarkable event took place on the streets of Tehran in 1978, and a community of people staked their lives in commitment to it. In this moment, the massive, impenetrable walls of global capitalism, market imperialism, and Westernizing modernism that surrounded everyday Iranians, tunneling them toward an inevitable future, floated up from the ground to reveal the glimmer of a different future. Was this hallucination, was it hysteria, ideological blindness? Was it Foucault’s hallucination or a collective one? I do not know. But we know that Foucault was so transformed by it that he committed himself to adopting an altogether different critical attitude in order to make sense of it.[25] He committed himself to becoming a kind of subject he never dreamed capable of becoming. Understanding and, if at all possible, re-engaging the motivation, stakes, and (perhaps) failures of this venture are far more instructive than rehashing leftist tropes to the similarly indoctrinated.

Whatever her relation to the past, the intellectual must be appropriate to the present she faces, and be open to the future that that present bends into focus. Perhaps no such intellectual or no such criticism exists today because the promise of a future has not been (cannot be?) recognized within our present moment. There should be occasions for a different criticism that need not supplant the ongoing efforts of the theorist Left, but open us all to different modes of recognition.[26] I contend that there is no shortage of knowledge produced by the academic, theory Left; what continues to be lost at the expense of that knowledge are more and better modes of acknowledgment. Knowledge of the past should be utilized to better the present, but we also need to remain alive to acknowledging possible futures within the present that past knowledge might stamp out.

Karl Fotovat received his M.A. from The New School for Social Research in New York, NY. He is interested in the first-generation Frankfurt School, German Idealism, and psychoanalytic theory.

Footnotes

[1] Janet Afary and Kevin B. Anderson, Foucault and the Iranian Revolution: Gender and the Seductions of Islamism (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2005). Hereafter AA. Note that Foucault’s original journalistic writings on the Iranian Revolution are collected in the appendix to this volume. My references are to the appendix exclusively.

[2] Behrooz Ghamari-Tabrizi, Foucault in Iran: Islamic Revolution After the Enlightenment (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2016). Hereafter BGT.

[3] BGT 60, also AA 220

[4] BGT 55

[5] BGT 163-5

[6] AA 29

[7] AA 189

[8] Michel Foucault, “What is Enlightenment?,” in The Foucault Reader, ed. Paul Rabinow (New York: Pantheon Books, 1984), pp. 32-50. Hereafter WE.

[9] BGT 168. While there is weak textual evidence for this in WE it should also be noted that Foucault remained conspicuously silent about his reports of the Iranian Revolution during the ensuing years, after its disastrous outcome.

[10] BGT 172, echoing Immanuel Kant’s pithy definition

[11] BGT 70-1, also AA 263-4

[12] BGT 171

[13] BGT 171

[14] AA 253

[15] AA 253, immediately following the preceding passage: “Furthermore… this collective will has been given one object, one target and one only, namely, the departure of the shah.” Cf. AA 222

[16] AA 209

[17] AA 209

[18] AA 205, citing Foucault: “‘What do you want?’ During my entire stay in Iran, I did not hear even once the word ‘revolution,’ but four or five times, someone would answer, ‘An Islamic government.’”

[19] AA 186, 205. One should note that Foucault’s understanding of Shiʿa doctrine was heavily influenced by Shariatmadari (as was Khomeini’s).

[20] Badiou's work on the subject qua subject of an Event, particularly his writings on St. Paul, are instructive here. The power of the protest by September 1978 had become so galvanizing that ordinary people, not just pockets of Islamic militants, recognized in one another a new community.

[21] The above formulation is textually supported by Kant but has been used more recently to describe Badiou’s concept of the Event.

[22] BGT 188

[23] BGT 166

[24] Was that not clear?—I ask cheekily. The current best option is to consult Adorno’s Negative Dialectics, 600 pages of some of the most opaque text written in the twentieth century. My point is simply that more and more readily accessible models are needed if contemporary criticism is to break from its own inborn, monolithic prejudices.

[25] BGT 58: “Foucault turned the transformative moment he experienced during the Iranian Revolution into a reflection and commentary on history. It is not farfetched to think that he regarded himself as one of those ‘new men’ that the revolution created on the streets of Tehran.”

[26] AA 267: “One must be respectful when a singularity arises and intransigent as soon as the state violates universals. It is a simple choice, but hard work: One needs to watch, a bit beneath history, for what breaks and agitates it, and keep watch, a bit behind politics, over what must unconditionally limit it. After all, this is my work. I am neither the first nor the only one to do it, but I chose it.”